The old Bloxidge Tallygraph website began as a primarily local history magazine, only later evolving an emphasis on community news. With this, the first of a new series of local history articles, its successor The Bloxwich Telegraph returns to that focus.

And it seems timely, with the 100th birthday of Dr Alan Turing, mathematician and father of computing, so much in the news world-wide, to begin with the tale of one of Turing’s colleagues – a man from Birchills whose work also helped shorten World War II through his work at Bletchley Park, and who deserves to be better known, particularly in his home town.

Some Walsall people have changed world history. One such was Francis ‘Harry’ Hinsley, born 26 November 1918, an ordinary working class lad whose analytical mind, talent and expertise were to help speed the winning of the Second World War.

Harry’s father, Thomas Harry Hinsley, was a waggoner, employed by the coal department at the Walsall Co-op. His mother Emma Hinsley (nee Adey) was a school caretaker, and they lived in Birchills, then in the parish of Bloxwich, Walsall.

Young Harry was educated at Wolverhampton Road Board School and later at Queen Mary’s Grammar School, Walsall, on a scholarship. A bright, quiet and studious boy according to friends, his academic bent and hard work resulted in his winning a further scholarship in 1937, to study history at St. John’s College, Cambridge.

Two years later, he was awarded a First in Part I of the Historical Tripos. Then, with Part II coming up and another First within his grasp, his life changed forever – and his historical studies were temporarily set aside.

One day, in the winter of 1939-40, Harry Hinsley was asked to see Martin Charlesworth, the Fellow of St John’s who, working with F. E. Adcock at King’s College, was running Cambridge recruiting for the Government Code and Cipher School.

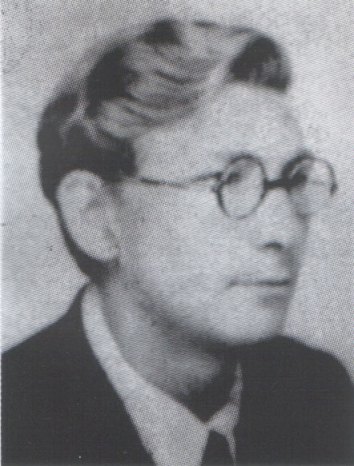

Harry was subsequently summoned to an interview with Alastair Denniston, head of the GC&CS, and despite his slight, bespectacled aspect must have made a considerable impression. Denniston immediately saw his potential and recruited him to serve in Bletchley Park’s Naval Section in Hut 4 (which is now a cafe as part of the Bletchley Park museum).

There, Hinsley studied the external characteristics of intercepted German messages, a process known as traffic analysis. From call signs, frequencies, times of interception etc, he deduced detailed information about the structure of the German Navy’s communications networks, and their navy itself. His powers as an interpreter of decrypts were also unrivalled and were based on an ability to sense something unusual from the tiniest clues.

Harry was frequently in contact with Naval Intelligence. But at first the Admiralty’s Operation Intelligence Centre paid little attention to the Bletchley codebreakers – a serious mistake. At the beginning of April 1940, the OIC ignored Hinsley’s radio traffic report of an unusual build-up of German naval activity in the Baltic, and as a result Britain was caught unawares by the German occupation of Norway.

Two months later he reported that a number of German warships were about to break out of the Baltic. Again he was ignored, leading to the sinking of our aircraft carrier HMS Glorious.

His warnings were covered up, but after this more attention was paid to Bletchley Park, despite continuing suspicions of profession jealousy and obstruction from some naval intelligence officers.

Radio traffic from the Baltic in May 1940 indicated that the mighty German battleship Bismarck (one of the two largest ever built by German) was about to leave, and Bletchley Park’s insistence that the Bismarck was heading for a safe French port was once again ignored.

Hinsley would not let the matter lie, and repeatedly telephoned the OIC after Bismarck’s fateful engagement with HMS Hood and HMS Prince of Wales, but it was not until 25 May that this conclusion was accepted. Just minutes after his last call, Hut 6 deciphered a message from the Luftwaffe Chief of Staff who was concerned for a relative on the Bismarck.

The response from this revealed that the ship was heading for Brest, France and with this information the Royal Navy closed in and sank the Bismarck on 26 May.

Many German military radio transmissions were encoded using the famous ‘Enigma’ machines, electro-mechanical devices combining a keyboard system and ‘key’ wheels with codebooks, making it extremely difficult to break.

But it was Harry Hinsley who, at the end of April 1941, identified the Enigma system’s fatal flaw. The same codebooks used on German U-Boats were also aboard their unprotected trawlers. These trawlers, transmitting weather reports to the Germans, also received naval Enigma messages. Hinsley helped initiate a programme of seizing Enigma machines and keys from German weather ships, significantly aiding Bletchley Park’s breaking of German Naval Enigma.

Towards the end of the war, Hinsley, then a key aide to Bletchley Park chief Edward Travis, was part of a committee arguing for a single post-war intelligence agency combining both signals and human intelligence. Eventually, though, the opposite happened, with GC&CS becoming GCHQ, still in operation today.

In 1946 Harry married Hilary Brett-Smith, whom he had met at Bletchley Park and in whose company he returned to St John’s College Cambridge where he had been elected a Fellow two years before. That same year he was awarded the OBE.

Dapper and small of stature, Harry Hinsley often had his leg pulled for the distinctiveness of his pronunciation (the Walsall accent, a variant on Black Country dialect, is famous in some quarters!) but proved an exceptional teacher, and in 1969 he was appointed professor of the history of international relations.

Hinsley edited the official history of British Intelligence in WWII, and argued that Enigma decryption had speeded Allied victory by one to four years. President of St. John’s College 1975-79, and from 1981 Master, from that year to 1983 he became Vice-Chancellor of the University. He was knighted in 1985, when his wife also became Lady Hinsley as a result.

Sir Francis Harry Hinsley OBE died at Cambridge on 16 February 1998. His was one of the most remarkable minds to come out of the borough of Walsall – and change the world. Not bad for a coalman’s son from Birchills.

Stuart Williams

Further research on Harry Hinsley is ongoing and this article will be extended in future. Watch this space!

Meanwhile, why not support the wonderful museum at Bletchley Park with a visit, as well as the National Museum of Computing there?